In 1990, two years after the first National Coming Out Day, I came out for the first time in print. I was terrified.

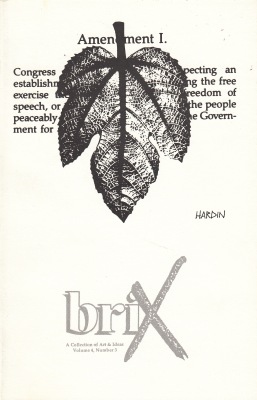

The venue was a small publication called briX, published by the Greater Flint Arts Council. As “a collection of art and ideas,” briX included poetry, short fiction, essays, and the brilliant one-panel cartoons of local artist Patrick Hardin.

At the time, I was 26. President George H.W. Bush was in the White House, continuing the political and social conservatism from the Reagan era. AIDS was sweeping across the country and into Michigan.

I wrote “Censor Your Art, Censor Your Life” in response to the choking anti-gay rhetoric of the Culture Wars. I wanted to explore, through a gay lens, censorship as a method of control and art as a mode of resistance.

Earlier this summer I had one of those unexpected, mind-jabbing conversations that are my lifeblood, the kind that wakes me out of my usual Flint numbness. Gary Custer and I were talking about the flag burning issue, and how the First Amendment gets trampled. A point he made that hit home for me was how odd it is that all sorts of things that are illegal, like murder, rape, stealing, or drug dealing, are OK to depict in movies, TV, books. Things that are quite legal and much more natural, namely sexual intercourse, are not OK to depict. I savored this notion, this newfound irony.

My own irony was that I hedged on offering how this idea applied to me. I’d only just met Mr. Custer and, although I’m fairly open, I’ve learned to be careful about disclosing one personal detail about myself, even to seemingly liberal folk. It’s like having a solo exhibit of paintings with the most intimate and beautiful one draped, to be shown only to select, trusted individuals (if at all). It was an everyday event, to censor my life.

Homosexuality has been a target of censorship for as long as there’s been censorship. Same-sex love was largely invisible, kept that way, until the 20th century. Since 1900, the year of Oscar Wilde’s death, examples of the repression of any art, any literature, dealing with homosexual feelings and activities, not to mention the feelings and activities themselves, have abounded.

I went on to recount examples of censored homo art, from the 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall to the 1933 painting The Fleet’s In by Paul Cadmus to the 1955 poem Howl by Allen Ginsberg.

The heart of the essay focused on contemporary censorship: the attack on Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart at Southwest Missouri State University; cancellation of an exhibit of Robert Mapplethorpe photographs at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington; the scourge of Senator Jesse Helms.

And I discussed the heartless revoking by the National Endowment for the Arts of grants awarded to four performance artists because their work was overtly sexual and queer. The censored artists—Karen Finley, John Fleck, Tim Miller, and Holly Hughes—became known as the NEA Four.

(I didn’t yet know that Holly Hughes was from Saginaw and I couldn’t know that I’d get to adore her close up when she got a teaching gig at the University of Michigan.)

“Censors want to ‘protect’ us, protect all of us, from some truth,” I wrote. “Whereas art selects and filters in an effort to find truth, censorship denies and perverts it.”

Reading the essay again 28 years later, I’m embarrassed by some of its sweeping language, such as my assertion that gay artists “purge their art of all that gives it real meaning.” Now I would temper the overreach: Too many queer artists purged their art of much that gave it real meaning.

The essay is an artifact, one that showcases the vehemence of enemies hell-bent on squelching truths and destroying lives. It is a curious primary source which captures a sense of suffocation of that time and in that place. It also documents my effort, however paltry, to break the silence, to break my silence.

I closed the essay by winding the discussion back around to my hometown.

Meanwhile in Flint most of the lesbian and gay population remains invisible and silent. Even those who are open are not very open…

Whatever overtly lesbian or gay art that appears locally is usually imported. So, we’re glad when the movie “Torch Song Trilogy” plays here for a week. We celebrate the paltry lesbian and gay section at Young & Welshan’s, the only bookstore in the area that even carries our books. And we’re so very grateful when Peter Marshall brings “La Cage Aux Folles” to Whiting Auditorium.

The unavailability of lesbian and gay art in Flint is sad because art is essential to human understanding. Art can show what it’s like to wonder if there’s anybody else in the world who feels like you do. Art can show how it feels to be wildly attracted to a guy and at the same time be scared he’ll beat the shit out of you if he finds out. Art comes closest to capturing love.

Then back to the personal.

I’m hyper-conscious every time I go to write something. When I pick up a pen I have to decide if I’ll allow my desires and dreams to show through. How much do I want to really explore what is basic to my being? Do I want to get tagged a gay writer and be delegated to one of several ghettos in the bookstore stacks? Do I want to be considered one-sided? Do I want to get called (ack) an activist? It’s like it’s a major decision to stop lying for one measly second.

I like that I used “measly.” It seems like such a Flint word.

Shortly after the essay came out in briX, I attended a party at my friend Vinny’s apartment. In attendance was a guy named Dale, who was something of a queen bee among that circle of friends. He was known for his savage old-school wit, like someone out of The Boys in the Band.

When I walked in the door, he bellowed, “Well if it isn’t Mr. Outspoken Homosexual!”

I remember feeling a bit of glee inside at his notice of what I’d written. I was still terrified at being so out in print, but felt somehow comforted by Dale’s affirmation.

The power of print! And now, the power of blogs! Love your work as always!

LikeLike