After a 10-month hiatus, I resume blogging here on an occasional basis.

For World AIDS Day two years ago, Michigan LGBTQ Remember highlighted twelve individuals that MSU alum and ACT UP member Jon Nalley knew from his college days who had died from HIV/AIDS as of 1991, when he recounted their lives in an affidavit to New York District Attorney Robert Morgenthau.

Last year, for World AIDS Day, retired AIDS Partnership Michigan executive director Barbara Murray shared twelve people from Metro Detroit that she witnessed in their living with and dying from the disease in the course of her career and activism.

I thank Jon and Barb for their sharing and generosity. I now have a stronger sense of what a big ask it was.

This year I remember twelve I knew: Tom Stephens, Michael Murray, Howard Yoder, John Brooks, Mark Chittle, Mitch Thomas, John Ferman, Michael Barto, Brian McDonald, David Sefernick, James Minterfering, and Curt Tramble.

They were friends and acquaintances and a couple strangers who died in the 1990s.

Other deaths in my life have brought me more emotional pain, but these AIDS deaths impacted me deeply. I experienced them with a sense of isolation from straight friends and family, who I thought could never know the connection and hurt and apprehension I felt. Apprehension at a time when there was no cure. And apprehension coupled with the intense yearning to flee my hometown.

My memories of them are all wrapped up with being gay in my 20s in Flint.

I conjure them in the chronological order that they passed from life.

From 1984 to 1988, Tom Stephens delivered the weather at 6:00 and 11:00 on WJRT Channel 12, Flint’s ABC affiliate. I lived with my grandparents at the time, and my grandma loved Chuck Waters on TV 5, so we usually watched Tom Stephens only at 11:00. The difference between the two weather personalities was that Tom was so, so fey.

I met Tom only once, at a gay party he held sometime in the late 1980s, maybe after he left the station and was heading the local humane society. My takeaway memory is that he took his hosting role very seriously.

My encounter with Michael Murray started off while I was at the Ms. Pacman machine at the State Bar on a summer afternoon in 1985 when I was 21 and he was 35. We took a couple stools at the bar and he bought me a Perrier. Deep conversation led to a invite to his home, which resulted, to put it discreetly, in some manual play. We made plans to go to the beach that next week, but when I called there was no answer, again and again. When I finally reached him, he said he forgot.

I got the cold shoulder and was bothered by the callousness. “I hate being a tissue. I hate being used and tossed away. Esp. in such a quick and deceitful way,” I wrote in my journal. “Oh well. I’m gullible too.” So yeah, I was just another conquest for him. For me, a lesson learned about gay male life.

As I noted in an earlier blog entry, I later heard Michael as a guest on the radio call-in show Flint Feedback and much respected his being out on the air.

I was saddened at Michael’s death in 1990 but felt, too, that I’d dodged a bullet by not going “all the way” with him. Not that he necessarily even had HIV when we had our afternoon rendezvous, just that I did feel a sense of relief to have been spared. Relief and sorrow and guilt spiraled through my experiences with AIDS deaths in the years after.

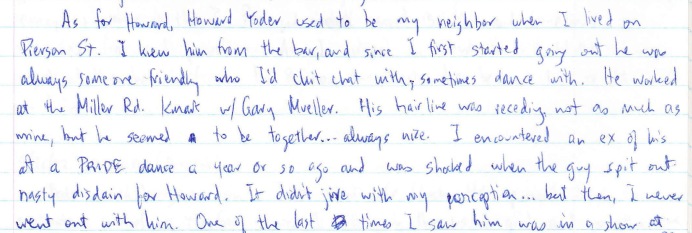

The first time I saw the body of someone who had died from AIDS was Howard Yoder at Brown Funeral Home. I’d forgotten how I knew Howard until re-reading my journal from that time. He’d been my neighbor on Pierson Street and was always a friendly person to chat with at the bar.

From my journal, May 19, 1992:

Consulted with Larry & Ralph, and Chuck about the protocol of whether I should visit the funeral home. Finally decided that despite not knowing his family, and only knowing him casually at the bar, I needed to go for me. I always liked Howard. Bruce Dietz knew him a little better than I did. They always danced, though they never went out. Bruce and I went to Brown’s after work yesterday. Howard was laid out in the same room my grandfather was. He didn’t look terribly emaciated. His trimmed beard lined his face, which was always rather cheerful, now still and caked with make-up.

I stewed over the moment for weeks. “It is all so strange and perverse and unreal. Unjust,” I wrote. “And I couldn’t help but feel dread, dread for the anticipated deaths of Wade, and Mark, and dear James. And who knows who else.”

John Brooks looked emaciated when I saw him in his casket at Swartz Funeral Home.

Mr. Brooks, as I’ll always remember him, was my junior high school counselor at Longfellow from 1976 to 1978. I put him in my Captain Vos comic book mainly on the belief that he was maybe going out with English teacher Ms. Roth. It was inconceivable to my 13-year-old self that someone I knew could be gay.

One of the first times I stepped foot in the State Bar, Mr. Brooks was seated on a stool up near the door. It blew my mind to see him there and learn he was gay. He was kind of aloof to me, which I viewed as snootiness but now understand as perhaps a form of self-protection at a time and place when the closet loomed so large.

I met Mark Chittle on my first trip to San Francisco in September 1990. His parents and my grandparents were best friends from way back, and his mom Jessie urged me to look him up.

Mark came out to his parents in the early 1970s and the first thing his mom said was, “I’m so sorry you felt you had to keep this inside for so long.” Mark’s friends loved when his parents came to visit because many of their parents had rejected them and Bob and Jessie were so accepting.

I remember Mark driving me up to Twin Peaks for a view of the city and showing me a pet cemetery beneath the Golden Gate Bridge. His favorite tombstone said, “Here lies Fluffy. She liked to have fun.” He then took me barhopping in the Castro. He loved his Cape Cods with Citron. I’d not yet heard of Absolut.

We were friends thereafter, and when he moved back to Michigan following his diagnosis we spent time together grabbing dinner, hanging out at the State Bar, going to Frankenmuth. Then, as he got sicker, he retreated and eventually moved up to the Tawas area. I heard through my grandma that he went blind.

After Mark’s death, whenever I’d see Jessie, she’d give me such gloriously intense hugs.

If snapshots taken by Copa owner Bill Kain survive anyplace, there’s a photo of me with my face painted by Tom White for Halloween one year.

I remember Tom mainly as a painter and prankster, part of a crowd of queer folk who resided in downtown Flint during nine months that I lived in the Carpenter Apartments on Grand Traverse.

I tagged along with Tom and a few others for a shopping trip to the old Smith-Bridgman department store on Easter Sunday 1984. Actually, we were scavenging, since Smith B’s had been closed since 1980 and was slated for demolition.

Our exploring that night also took us to an old fallout shelter in the basement of Hubbard Hardware that had metal barrels of water and tins of soda crackers and rock candy from 1962. Tom joked, “The nuclear bomb could go off and the only survivors would be four faggots and a woman with a hysterectomy.”

Jump ahead to a New Year’s Eve sometime in the early 1990s, when I ran into Tom, now going by Mitch Thomas, at a crowded party in the basement of the Stockton House, an old brick Victorian home on Ann Arbor Street.

Mitch looked thin, visibly sick. When I talked with him, he lamented that now that he had the plague, nobody would touch him. He told me how he wished someone would make love to him “one last time.” I found his unmet physical and emotional hunger heartbreaking.

I met John Ferman on my 17th birthday. My friends the Atwoods arranged for me to talk with him in their living room as I was struggling to come out. John was a gay congregant of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church where Fr. Bob was deacon.

Rather than getting a sense of assurance, however, I came away feeling that prospects for queer youth in Flint in the early 1980s were bleak. The town’s main gay outlet was bar life, and I had to be 18 to set foot in the State Bar or the Copa.

Two years later, in March 1983, I got up the nerve to ask John to take me to the Copa. The evening started at his apartment, which was memorable for its glassed-in front porch overflowing with plants. John was an obsessive Judy Garland fan and he was having a viewing party for the annual TV broadcast of The Wizard of Oz.

At the bar I ran into Jimmy Clark, a classmate from junior high, and his pal Philbert. I remember dancing to Madonna or Cyndi Lauper. John was probably annoyed that I went off on my own. I think he saw it as a date. It wasn’t.

John and his roommates Jim and Miss Bobby became my downstairs neighbors when I moved into his apartment building that fall.

Michael Barto was one of those good-looking guys that left me blindsided when I discovered he was gay. It didn’t seem possible.

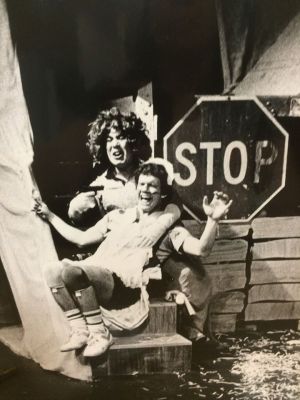

He used to come into the Flint Public Library where I worked. At the time we were both students at the University of Michigan-Flint and I saw him perform in a Theater Department production of Balm in Gilead, the same show in which my friend Kristin played a biker chick.

I never really knew Michael but I knew people who knew him.

Tom White was once his roommate at the Bervean, an apartment building on Second Street where Philbert lived. Tom gossiped about Michael’s reputed attributes.

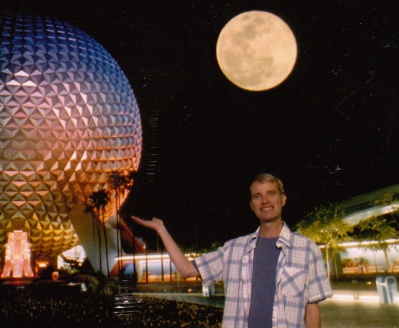

Some years later, when Michael was back in town for The Wizard of AIDS, being staged at Buckham Alley Theater, he was sporting a mustache. Very he-man.

Brian McDonald had a lilt in his voice and an “aw shucks” charm about him.

My earliest recollection of him is his deejaying at the El Matador as I danced with Joe Feliciano and others in a circle embrace to Joe Jackson’s “Real Men” circa early 1983. Kind of formative.

Brian was in the cast of Alice!, a delightful UM-Flint black box play based on the Lewis Carroll books (and directed by Michael Barto).

Another Brian memory is his telling the story one night about being followed from the State Bar by a carload of menacing thugs. The tailing turned into a chase, at which point Brian drove to police headquarters. The thugs took off.

His mom Joyce was co-founder of Flint’s first incarnation of PFLAG.

Brian appeared in Michael Moore’s 1989 documentary Roger & Me in footage Moore used from the visitor’s bureau where Brian played a gas station attendant giving directions to out-of-town tourists.

A winter blizzard kept me from driving to Flint from Ann Arbor for his funeral. I still regret not attending.

I previously discussed dear David Sefernick when I wrote here about Gay Funerals, how his mom Bea worked with my Aunt Melita and how I ran into him wearing a Silence = Death t-shirt once at the Torch.

In September 1995, I recorded an interview with David, in part for an article entitled “Industrial Strength Queer” for Between The Lines and in part as an oral history. He stipulated that I not use his real name for 20 years. More than 20 years have now passed.

David talked frankly about his alcoholism and drug addiction and abusive relationships. He’d only recently learned he was sick, not simply HIV-positive but with full-blown AIDS, and spent 32 days in the hospital. “My esophagus was almost eaten up,” he said. “I couldn’t even swallow water.”

He was embracing his time left as best he could, taking watercolor classes and meeting new people. He’d played piano for many years but sold his when he was desperate for money, so he was thrilled that a friend of his mom’s gave him a keyboard.

Foremost, David was distressed by how oblivious people he met at the bars in Flint were to the epidemic:

I met this one person. I went somewhere with him and I was very, very careful. Basically, all we did was hug. It’s like they want to do more and I won’t let them, because I’m not going to— People are so stupid in this town. They think it’s still not here. It’s like, “You guys, if you only knew. You’re looking at someone with AIDS.” I don’t look sick, but that don’t mean nothing. I’m sick as shit. Why are you people so stupid? These people want you to do things with them that you could only do in 1970. You can’t do that stuff. And it scares the hell out of me.

I last saw David at the NAMES Project in DC during its final full display on the Mall, a few months before he died.

James Minterfering was adorable.

I asked James out and he turned me down.

Exactly a year later, after losing weight and getting buff, I asked him out again and he said yes. We dated for about three weeks. I palpably remember, in the midst of some heavy kissing, him pulling back and telling me he was HIV-positive. My immediate emotions were bewilderment and intense sorrow. But mostly I felt deep, deep admiration for his having the courage and integrity to reveal this to me.

Over the next several days I grappled with this new reality and concluded that it didn’t detract from wanting to continue with a relationship. He broke things off shortly afterward.

We remained friends, something I was deliberate about. I sprang for his flight to attend the OutWrite conference in Boston. And we took parachute training together down in Tecumseh, though he backed out on the actual jumping from an airplane.

Mark Chittle rode with me when I did my jump and watched from the ground.

James, too, was at the 1996 NAMES Project display in Washington where I last saw David Sefernick, but I didn’t run into him there. I recall my friend Rob saying I should be grateful I did not see him, that serious dementia had set in and that’s not how I should remember James.

When I worked on the Information Desk at the Flint Public Library, Curt Tramble used to come by and chat after he got out of classes in high school. I don’t think either of us ever came out to the other. Yet the fact that we were both gay was our unspoken impetus for conversing.

I must’ve seen his death notice in the Flint Journal in 1998 on a visit back to town to see my grandma. So sad for his death, and sad that we’d lost touch over the years.

A quarter century or so has passed. The obituaries that I clipped are all yellowing now.

I know that my memories are filtered through the hubris of the living. But as my recollections recede in clarity, I feel a responsibility to remember these men and to capture the loss of them in words.

Others certainly knew each of them better than I did. I hope some will share their memories here or elsewhere.

Thanks for the memories Tim. I love your writing. Good vibes on this World AIDS day and happy holidays!

LikeLike

Thanks for these sad and loving fragments from your Flint quilt. Yes, you are a survivor, and that took some luck and some work. But the hubris of life has offered you the great opportunity to tell the lives of those who have passed and to appreciate the world as it has changed since those times. Thanks for writing, keep it going…..

LikeLike

Love this post so much, Tim. Thank you for the lovely tribute!

LikeLike

Tim, brilliant writing and impressive memory as always. You and I share common connections with many of these men and the loss is still palpable. I think they would all be touched and honored by your remembering of them.

LikeLike

I know this is an older post, but I just wanted to thank you for the beautiful tribute. I also wanted to add a little story about one of the men you mentioned. Tom Stephens was my very first boyfriend. We dated in 1988. He was the kindest man that I had ever met and the love of my life. I won’t say why we broke up, but we did. About six months after we broke up, I received a phone call from a mutual friend telling me that Tom was HIV+. Tom asked the friend to give me his number and call him, but I was too stubborn and still hurt from the breakup. I told our friend to tell him that if he wanted to talk, he could call me, and if he did, I would be there in a heartbeat. But he was stubborn as well. We never did talk again, and then I received the call that he had passed away. I went to the funeral, and they let me have some time alone with him. It was the hardest thing that I had to do at the age of 22. Saying goodbye to the man that I loved. I still have the last letter that he sent to me, and I still have a copy of his resume. His picture sits on my entertainment center, even after 30 years. And I still visit his grave. I still think of him often, and still love him.

LikeLike